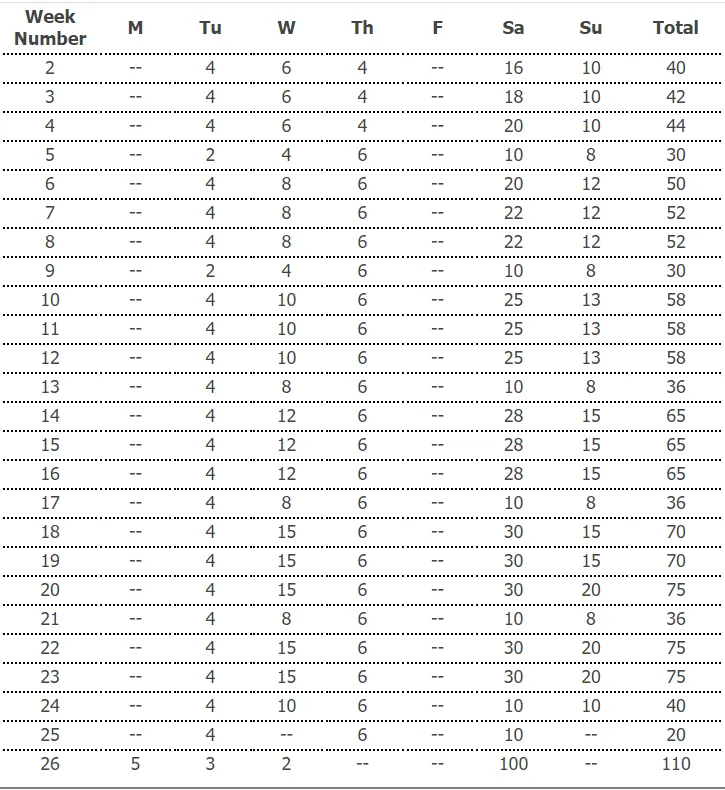

Ultramarathon in NYC

Cross-posted from my Medium article. Highly recommend reading on Medium as it’s a long read and the formatting is better there.

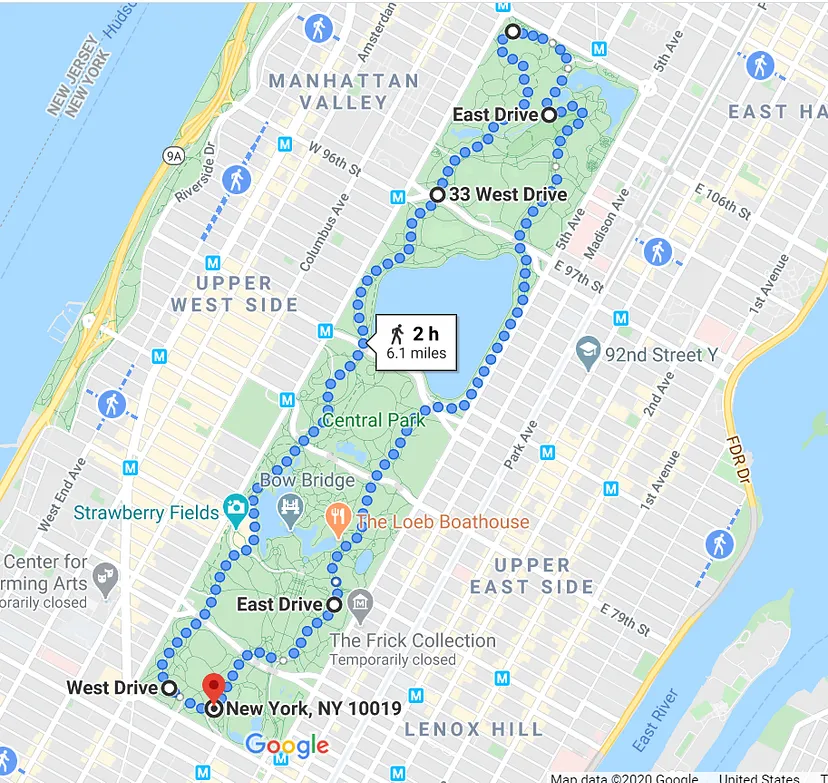

On Saturday June 20, 2020 I completed my first 100km ultramarathon running alone in Central Park.

I then spent the next two days doing what all runners do: resting tired feet at home, indulging in a couple of nice meals and of course, sharing the news with friends and family to bask in that oh-so-sweet sense of respect and admiration. But what I found most surprising was that unlike running my first marathon, the ultra didn’t bring with it an overwhelming sense of pride in what I had accomplished. Not that I wasn’t proud of what I had done, but the feeling was a lot more muted, balanced with an understanding of the commitment and sacrifice it took to get there and how anyone could do it with the right mindset. Thus, the purpose of this article is to both serve as a journal and a guide. A journal for me to reflect on what I gained from the experience and give you a few reasons to consider running an ultra yourself. A technical guide for the aspiring first-time ultramarathoner to hopefully avoid some of the mistakes I made.

Background

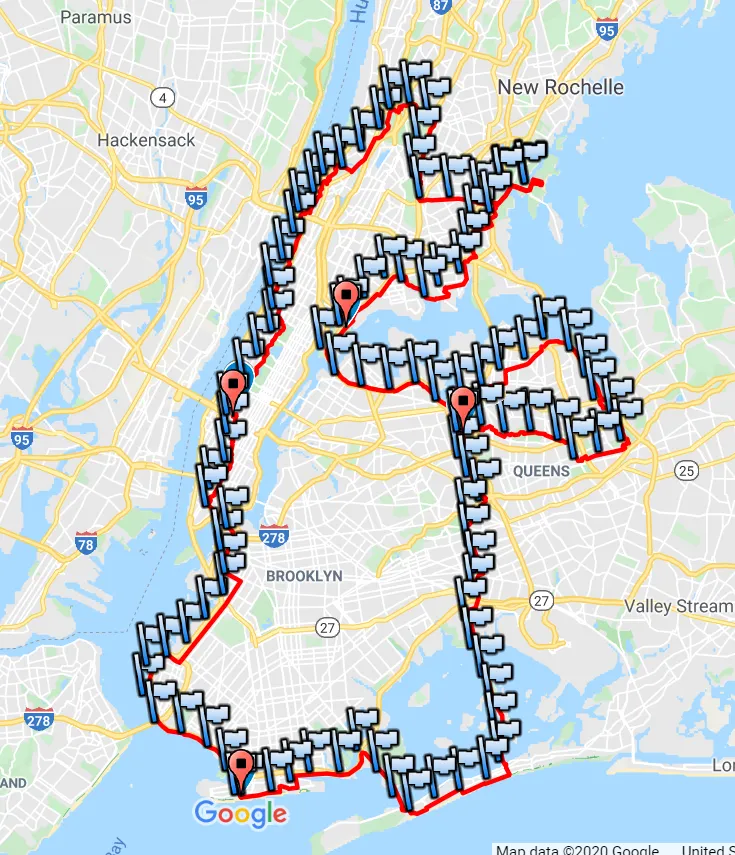

Some time in December 2019, I signed up for The Great New York 100Mile/100Km Running Exposition. It was a 100 mile race around New York City scheduled to take place on June 20th 2020. Starting in Times Square in Manhattan, you would run up North into the Bronx, South-East into Queens all the way to Flushing, double back into Brooklyn, run through Coney Island before turning back into Manhattan and finishing in Times Square again. The race was 100% urban on concrete pavement and close to zero elevation change. There was an option to decide two weeks before the race date whether you wanted to run the shorter 100km race, but I started training with the intention of going the full 100 miles.

Then COVID-19 happened and everything got canceled, including the race. By this time I was about 5 months into the training and didn’t want it to go to waste, so I resolved to run the distance myself on the date anyway. On the date itself, I cleared about 56 miles before experiencing a sharp pain on the arch of my left foot. It persisted through an hour of me trying to walk it off and it was at that point I knew I had to call it quits. But being extremely stubborn, I insisted on hobbling another 6 miles to clear 62.5 miles (100km), the shorter race. It was a brutal 2 hrs that took 4 days to fully recover. Hopefully with this guide you won’t make the same rookie mistakes I did and successfully complete your race. But first, we need to ask a very important question.

Why run an ultramarathon?

A better question would be ‘Why do anything at all?’. Life is short, and most people at some point in their lives will start to acknowledge a simple truth. Choosing a difficult challenge for yourself, doing the necessary preparation and ultimately struggling to achieve your goals is part of what gives our existence some meaning. In doing so you get to learn about yourself and the world. Out of the vast expanse of the possibility of human experience you get to pick a small corner and dive really really deep. And the reward of the expedition is experience the beauty of the trip yourself, without living vicariously through the stories of others.

If you already do some casual running and are seeking a challenge for yourself, I recommend giving an ultra a shot. You might not be the lifer who still runs long distance well into his 60s. This might in fact, be your only ultramarathon experience. But I guarantee you will not regret having done it.

A couple of caveats though. Running an ultramarathon will not help improve your marathon performance. The speed at which you run your training runs will easily be several minutes more per mile than your optimal marathon pace. You will also need to adapt your body to constant refueling during a run, something that’s not necessary during the shorter timeframe of the marathon. It is also a huge time commitment that will eat away your entire Saturday AND Sunday morning for several months on end. There will definitely be a lot of pain and times where you feel like calling it quits, but there will also be moments of pure bliss, clarity of thought and a flow that you get only when you fully immerse yourself in something.

Fitness foundation and preliminaries

An appropriate baseline benchmark should be a marathon. If you have not already done so, I highly recommend you complete at least one regular 26.2 mile marathon before starting an ultramarathon. It will build the foundational stamina to survive the ultra training runs and for first-time runners, it gives you an idea if this is something you’d be willing to pour hundreds of hours of training into.

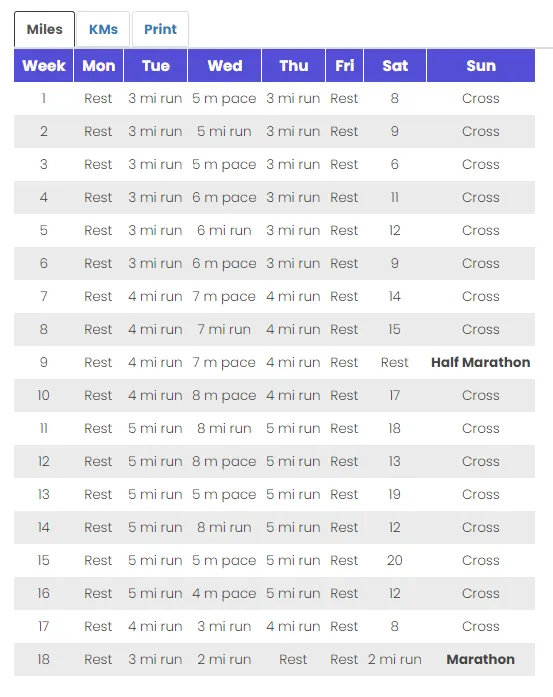

It takes between 3–5 months to train for a 26.2M starting from scratch, depending on your baseline fitness level. A good training plan can be found here. I personally used the Novice 2 training plan for my first marathon, but whatever plan you use is not as important as having one and sticking to it. The goal is to outsource as much of the planning as possible so all you need to do is show up and run.

After you’ve done that, it takes an additional 6–7 months of training to build up to 100M. Find an online plan that caters to ‘newbies’, preferably one that just focuses on mileage without cross training or speed-work days. I find this makes training a lot simpler and is a lot closer to the real ultra experience. I used this plan. If you’re running a shorter distance like 60M, I still recommend this plan, as the focus is on building up stamina over weekly mileage and the daily mileage is never above 30M.

Now the easiest way to complete an ultra is in an organized race that will take care of the annoying logistics for you: refueling, water, timing, etc. Having a group of people running the same distance together also provides a gigantic mental boost that will make the ultra mentally more bearable. So go sign up for an ultra about 7 months from when you want to start training. I recommend taking the recommended training plan and adding 2–3 weeks to it. That way if you injure yourself or go on vacation to somewhere where running isn’t an option for whatever reason, you have some buffer time to pause the training. If you finish the training with time to spare, just repeat the week with the heaviest mileage, but be sure to leave time for the taper down before race day. If you can convince a friend to run an ultra with you, I recommend doing so. The harsh reality is that the two of you might not end up running the ultra together if your ‘natural’ running paces are not close, but at the very least you will both have someone to keep you accountable to your training.

If you have a medical history that might make running difficult, e.g. asthma, brittle bones, etc., it goes without saying that you should consult a doctor before doing any of this. If you are overweight or even just slightly on the chubbier side, I would recommend going into the training with a plan to lose some weight, primarily by restricting your caloric intake, as it will reduce the impact on your knees and ankles and make your running that much easier. I will talk about how to do this in detail later.

Training equipment

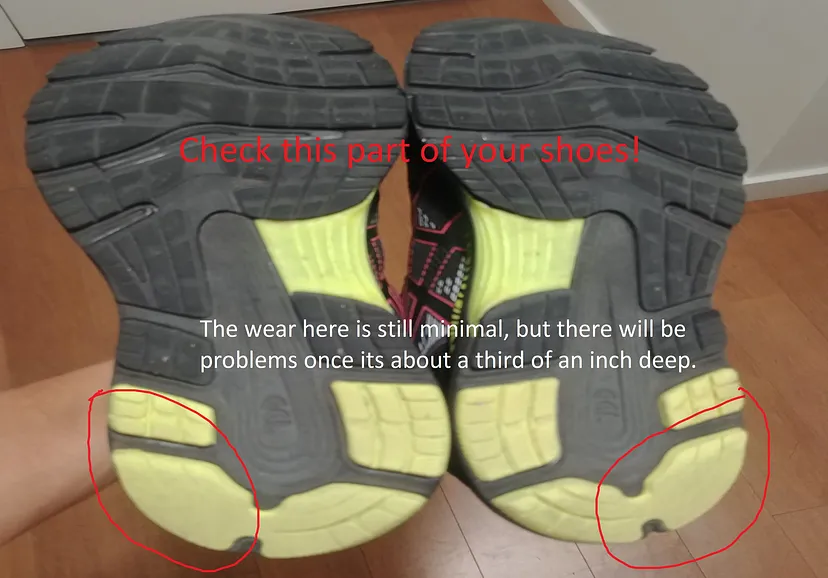

If you remember only one thing from reading this article let this be it: Your shoes are the most important thing when it comes to long-distance running. You should always be training in proper running shoes and changing them when the base (usually the heel) starts wearing away. When this happens exactly depends on your gait, weight and running surface, but usually around the 300M mark. Failure to change your shoes will result in your heel slightly mispositioning itself each time your feet land on the ground. For short distances this is fine, but for 20M+ training runs it compounds and will result in injury and a lot of pain — trust me. If you have the means to do so, I recommend going to a dedicated running equipment store and getting a good pair of shoes tailored to your gait, foot shape and desired cushioning and support. Keep this nice expensive pair of shoes to wear during race day, but remember to break them in during the tapering. You can then buy a cheaper pair that’s similar in size/shape for training and stick to the same model each time you replace them. During race day, your broken-in shoes should be as new as possible to minimize the chances of injury and a DNC (Did Not Complete).

Socks-wise everyone has their own favorite type. I prefer cotton ankle-lengths. But be aware that shorter socks tend to have more debris falling in when you run on dirt and gravel. It eventually becomes very annoying to deal with.

I recommend Dri-Fit or any thin breathable material for shirts. Cotton will absorb your sweat and cheap polyester will trap body heat. Both are a no-no for long runs where comfort is key. You can tell the difference between good and bad polyester shirts by the size of their weave and the thickness of the material.

For pants most running shorts are fine. Training for an ultra is different from a marathon in that it will likely span over multiple seasons. You might need to change to running tights or add a jacket depending on the weather. Furthermore, the race itself will span over a full day, so I recommend dressing for the hottest part of the day (typically afternoon) first and putting on extra layers only when necessary. Depending on climate, this may not actually be necessary.

Depending on how much and where you sweat, you might consider using a sweat band or nipple tape. Wearing glasses myself, I find silicone ear hooks to be very useful for holding them in place. Sweaty armpits, calves or crotches can cause chafing, and applying vaseline early is recommended.

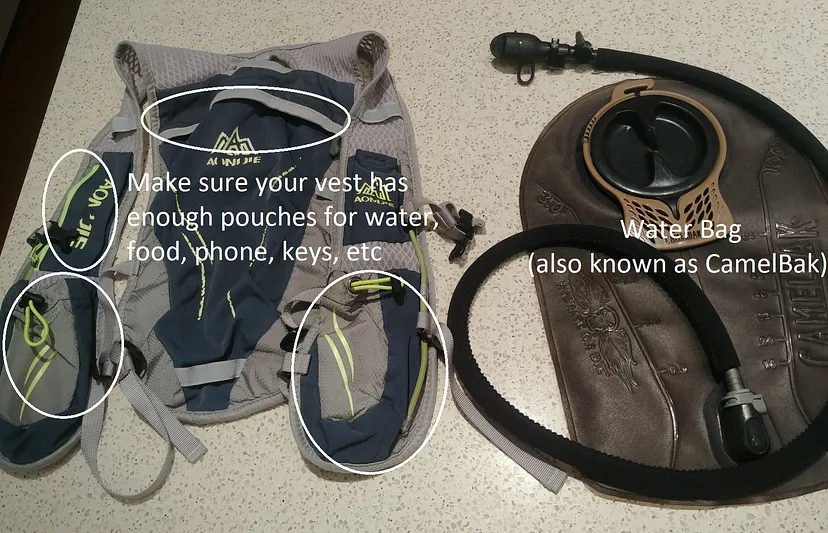

Finally, we have the long-distance running gear. You will need a lightweight running backpack that’s form-fitting and has several pouches. It’s also known as a hydration vest. Its primary use will be to make sure you always have water on you between the aid stations, which are often spaced several miles apart. It will also store your keys, phone and a small amount of spare food (e.g. Clif bars, energy gels, etc) for emergencies. Always run with your pockets and hands empty whenever possible. Depending on the type of race you signed up for, you might also need to carry additional gear such as a head torch, a map or a running jacket for the night section. Arrange to pick them up at an aid station if the race rules permit.

One thing I found surprisingly convenient was to switch from water bottles to a water bag (aka Camelbak). Running with a weight on your back will feel slightly uncomfortable initially, but the convenience of drinking directly from the water tube will more than compensate for it. As a few added bonuses, you can carry more water with you and don’t have to worry about weight distribution when you drink from one bottle but not another. After a few months of training, you will get a feel for how much water you need between each aid station, and you might not need to train with a full bag.

For certain races with large elevation changes, you might consider racing with hiking poles. I personally have never used these for running, but I have noticed them to be quite popular for mountainous trails. You can even get collapsible ones that strap onto your running pack.

Not every piece of equipment needs to be bought immediately. If you run in a park, there might be water fountains available that eliminate the need to carry water. But as much as possible, you should train in a similar environment to the actual race, wearing and carrying your full race gear. I recommend doing this at least a month before the event itself and, if possible, right from the start.

Form and pace

There are two major skill components in ultra running: Form and Pace. They will differ from person to person, though there are a few general rules. The goal of your training sessions should be to find the techniques that work best for you.

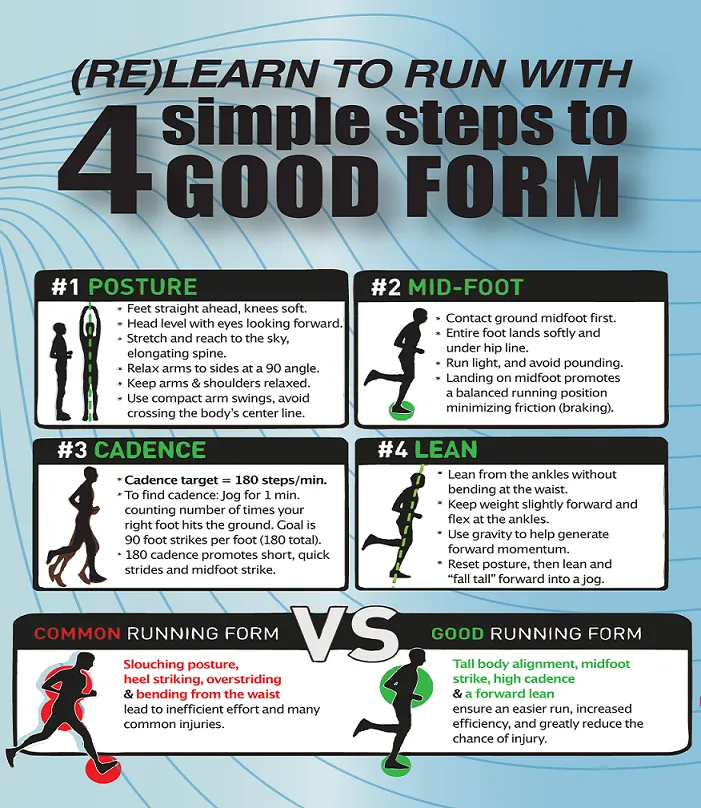

Form is how you run. It encompasses your spinal and hip posture, the length and position of your arm swings, which part of your foot strikes the ground first, stride length, breathing, etc. My recommendation here is to watch a couple of YouTube videos of people demonstrating the ‘proper form’ for long-distance running, then try implementing some of their techniques during your training. But if you find they don’t work for you, feel free to experiment around until you find something that does. You do however, need to keep a few things in mind.

Whatever position your body is in needs to be very comfortable, especially for the arms, as you will be holding that position for many hours. Changing certain behaviors like breathing patters and stride will be more difficult than you expect. It takes a considerable amount of mental focus to breathe or step a certain way. When you inevitably become distracted or tired, your body will default to ‘autopilot’ and do what comes naturally instead. You will thus need to continually practice that specific behavior until it eventually becomes part of the ‘autopilot’. What I found worked well for me that you can also try, was to instead run normally without thinking about the form at all. You can listen to music, observe your surroundings or think about your personal life if you want to. After about an hour or two, your body should get warmed up to the point where it realizes it’s doing a long-distance run and adjusts itself to a comfortable form. At this point, you should try to make a mental note of your current form and try to run this way right from the start of the next training session. It will take a little bit of trial and error to get this right, especially as your stamina increases and muscles strengthen over the following months. This is also how you find your ‘comfortable’ long-distance pace.

When it comes to pacing, the goal is sustainability. You should really only have two tempos: jogging and walking, and be able to switch between both on command. Depending on whether you’re walking uphill or walking over a flat surface, your actual speed will change, but your rhythm and form should feel the same. As much as possible, you want to stick to these two tempos during all the training runs. It is very tempting to run faster during the short 4-6M training runs, but the goal here for a newbie is to get your body and mind used to high volume at your ideal jogging pace.

Unlike 5KM/10KM runs or even marathons, you will at some point need to walk and there is no shame in doing so. Almost all ultra runners will walk at some point. Remember that your walk should still have good form, and if possible, be slightly brisk. Walk all the ascents and any steep descents. When you are walking, it is a good time to eat, rehydrate, apply vaseline, scratch yourself, all while moving. Walk early. If you find yourself only walking when you’re exhausted and can no longer jog, it is too late. For races on mostly flat terrain, you should still incorporate some walking. In lieu of doing it randomly, try Jeff Galloway’s Run-Walk-Run method where you alternate jogging/walking in fixed time intervals. 25/5 or 20/5 (minutes) are popular ultra ratios.

Talking real numbers, your jogging pace should be somewhere in the 5-6.5 miles/hr range. It’s possible to be higher, but make sure you aren’t straining your muscles and your heart rate is low. If you’re on the high end of this range, I’d consider walking more frequently to minimize the fatigue buildup. On the lower end of the range you need to be careful, as your average speed will decrease after you factor in the time you spend walking. While this might seem harsh, you also need to account for the time you spend resting and eating at aid stations, as well as general fatigue later in the race. Staying within the above range will give you a decent buffer to finish the race on time.

Food and Water

It is important to hydrate yourself frequently during training. You’ve probably heard this line multiple times already. It is completely true. Running while dehydrated increases your risk of injury and the rate at which your muscles accumulate fatigue. The problem most newbie runners face is the reluctance to either carry water outright or to stop and drink mid-run. I recommend carrying a water bag in a running vest to keep your hands free and the water easily accessible.

Before we discuss food, let’s first talk about the infamous runner’s wall. Many people who have run marathons or trained for them will be familiar with this phenomenon. It is characterized by the sudden onset of immense fatigue and weakness in the legs. This happens when your body depletes its glycogen storage.

When we run, our body draws energy from two main sources: metabolizing fat and breaking down glycogen. The intensity of the exercise determines the ratio between the two, with more intense workouts drawing more energy from glycogen as opposed to fat. Our body replenishes its glycogen storage through the consumption of carbohydrates. This can either be done during the run or before the run, where it is commonly known as ‘carb-loading’. While carb-loading might work for shorter distances like marathons, I would not recommend relying on it for distances above 60 miles. The reasoning is simple: you won’t be able to load enough carbs to sustain the entire race, and are better off adapting your body to refuelling during the run itself.

I did a lot of research on this for my training, so let’s dive into some simple math. A 150lb runner burns around 110 calories per mile. For a 60 mile race, this is 6600 calories. An adult male consumes roughly 2500 calories per day. Adding the daily requirement to the running calories translates to a caloric requirement of 3 days and two meals worth of food. This is how much you “should” be eating during the race day to be in caloric equilibrium. Even if half those calories come from burning body fat, you can quickly see why carb-loading the night before will simply not be enough.

But this is why fat is so powerful. 1 lb of fat stores roughly 3500 calories. A 15% body fat percentage on 150lbs translates to 22.5lbs. That’s a lot of stored calories. If you are like me and don’t enjoy eating during a workout, then you want to minimize the amount of food that you will eventually need to force-feed yourself. This means you should be jogging at a low-intensity, relaxed pace, which will maximize the proportion of calories metabolized from your body fat. You will however, still need to eat eventually, as there will always be some proportion of calories consumed from your glycogen.

So how much do you need to eat during training? Jogging at a comfortable 12mins/mile, this translates to 550 calories per hour. For low to moderate intensity exercise, you can be anywhere from 50–75% of your maximum heart rate, depending on your fitness and genetics. This translates to anywhere between 60–35% of the calories burned coming from metabolizing fat. I know it’s a wide range, but the natural variance here is pretty high. Let’s just say that roughly 50% of the calories will come from your glycogen stores, which means you need to consume roughly 275 calories per hour.

What you choose to eat is up to you, but it should be something you enjoy eating. I went with Clif Bars, but I have heard of people eating peanut butter sandwiches, cake rolls or salted pretzels as well. Just try to avoid protein bars and energy gels. You want your food to be high in carbohydrates, some of which can be sugars, and I’d also advise getting your stomach used to eating solid food during a run. Surviving an ultra on liquid calories alone is not fun.

It is extremely important that you practice eating during the training runs. Try to eat whilst walking rather than stopping completely. Immediately after eating, there might be some initial discomfort while jogging as your stomach is digesting, but it will eventually disappear as you get used to it. If the discomfort is severe, it is better to switch to walking until it dissipates rather than powering through. The key principle here is sustainability. On that note, I try to eat before/after the training runs as I would a normal day. This means no carb-loading and eating perhaps only a slightly larger portion of breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Finally, the last dietary component you need to watch out for is salt. Runs that span more than 3 hours, especially in midday heat will cause you to sweat. Drinking lots of water can rehydrate you, but will not make up for the body’s loss of salt. Over time, this can lead to light-headedness and fatigue, but more likely, muscle cramps. A common solution is to occasionally drink some Gatorade or any sports drink with electrolytes in it. You can also opt for eating some salty food and downing it with plain water.

Race day and pre-race day

Prior to the race day, there are a few things you can prepare to make your life slightly easier.

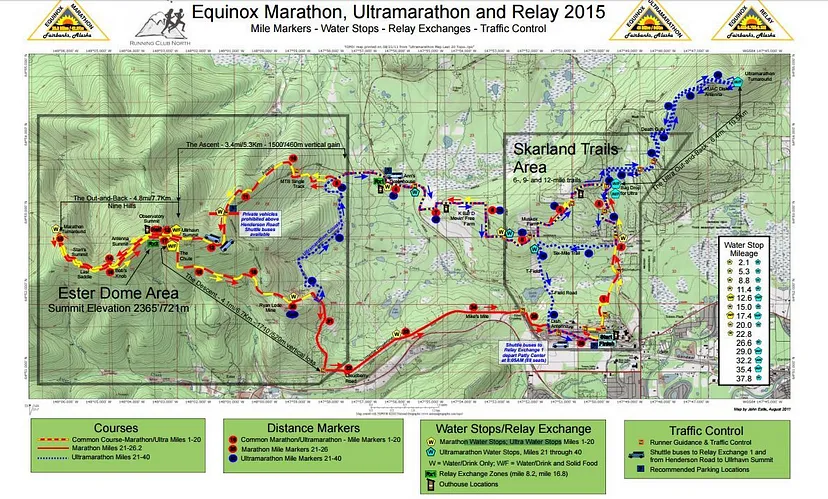

Study the course map to understand the distances between checkpoints and elevation changes. Have a rough estimate in mind of when you plan to reach these checkpoints. Based on the distances between checkpoints, calculate how much water you need to be carrying at each stage. If it is convenient to do so, scope out the course in advance and run sections of in during your training or tapering runs.

If the race starts especially early in the morning, adjust your sleep cycle at least a week in advance.

In some races, the checkpoints will be manned by the organizers and you won’t need to have your own resupply crew. However, it is recommended that you ask your friends and family to meet you at the various checkpoints anyway. It will provide a lot of psychological support. You can also ask them to bring specific snacks for you, or a change of running kit for when it gets colder/warmer (check that your race allows this). If having people around is logistically difficult, then arranging to call them when you reach the checkpoints is also a good idea.

Do not eat any spicy foods or anything outside your normal diet the day before the race.

If you are not running the ultra with a friend, consider reaching out to some of the participants to find someone who runs at a similar pace to you. If possible, meet up in advance and run together to check the pacing. Having some company on the ultra will make it much more bearable. Remember, as newbies, we’re not looking for speed but to maximize our chances of completing the race in time.

If you put in the work and trained properly, your chances of success will be determined by whether anything goes horribly wrong rather than individual things going well. What this means is that your armpits might start chafing earlier than expected, your legs get tired a bit sooner or you spent more time at a checkpoint than you had intended. All this is fine. You’ll still be able to finish. But if you twist an ankle, suffer a heat injury or tear a muscle somewhere, you will very likely have to drop out early. What this means is that you need to exercise caution, and not be afraid to slow down or take extra recovery breaks where necessary. A good rule of thumb is that if your body tells you something, you’re allowed to ignore it once or twice. But if it tells you the same thing over and over again, you had better listen.

Training technicals

A few ideas that I think are good for training.

- Terrain on long weekend training runs must match the race terrain. If possible, do so for the weekday training runs as well.

- Absolutely no skips unless you are sick, injured, or in a location where training is unsafe. As a newbie you need all the training you can get, regardless of how late you stayed in the office, how tired you are or whether it’s raining outside. But do not train when you are injured, as this will only set you back further. If you must pause the training, continue where you stop and do not jump ahead as you need the gradual progression.

- The goal of the training run is not to finish quick, but to finish comfortably. You should be in good physical condition to repeat the entire distance if necessary. This means that even on the shorter 12M training runs, I choose to run/walk/run so I can finish as fresh as possible.

- Plan your running routes in advance so you don’t have to worry about counting miles during training. Finding a park or running trail close to home is recommended for weekday runs. Running the same loop or path frequently will help you keep track of your distances and speed.

- I typically run in New York City while listening to music on headphones. But this might not be allowed, you might not have enough battery to last the full duration, or you might just decide to enjoy the sounds of nature for your race. Either way, if you are like me, you will need to allocate a few weeks to slowly weaning off the music. You will get bored more frequently and be more aware of pain in various parts of your body, definitely not something you want to discover for the first time during your race.

- Training your mental discipline is important. At times, it will be tempting to speed up when you see older folks run past you. You might think of cutting training short when it suddenly starts raining midway. At all of these moments, think of it as fortitude training, as no matter how bad you feel during training, you will probably feel five times worse at some point during the actual race, and you want to have the mental wherewithal to soldier on when that happens.

- Try to attune yourself to your body. This involves straddling the fine line between testing your limits during training and getting injured and setting your training back a week. It’s also knowing when you need to stop to refuel/rehydrate, when to switch to a different stride, when to take another break based on terrain, humidity, temperature and how your body feels at the time. Sadly, this only comes with experience, so I recommend making different choices each time until you find out what works for you. Don’t be afraid to get a bit hurt during training — that’s what training’s for. Just make sure you learn from each mistake.

- The greatest reward of training is reaching what I call a state of flow. After a few months, your running pace will settle and there will be no need to constantly check the time. You should be running at a relaxed pace that won’t labor your breathing or generate enough pain to distract you. This is the moment where your thoughts will start to drift. Sometimes you become more observant of your surroundings and have an overwhelming sense of being present in the moment. Other times you find yourself thinking about a problem that you’ve been struggling with for a while and suddenly have the clarity to approach it from a different direction. Very often, you will think about your values, goals and direction in life and end up having a deeply intimate conversation with yourself. This mental state actually happens quite frequently during aerobic exercise. I suspect it has to do with the release of endorphins and the triggering of your body’s fight-or-flight responses. Finishing your race is ultimately the goal of your training, but I think this is part of what people mean when they say it’s all about the journey and not the destination.

Epilogue

After the race, your body will be sore for a couple of days. This is completely normal. Take a well-deserved break from training. If, like me, you basically stopped all upper body training during the 6 months and you want to pick it up again, remember to ease into it slowly. You will likely be significantly weaker than you expect. The long distance stamina will stick around for a while, but unless you have been running long distance consistently over several years, it peels off very quickly after about 2–3 weeks. If you have the time, doing at least one long run a week will slow the deterioration. It is also a good way to transition to shorter race distances without starting the training from scratch.

I hope this guide has given you a better idea of everything that’s involved in preparing for an ultramarathon. If you are running one, I wish you the best of luck in completing it.